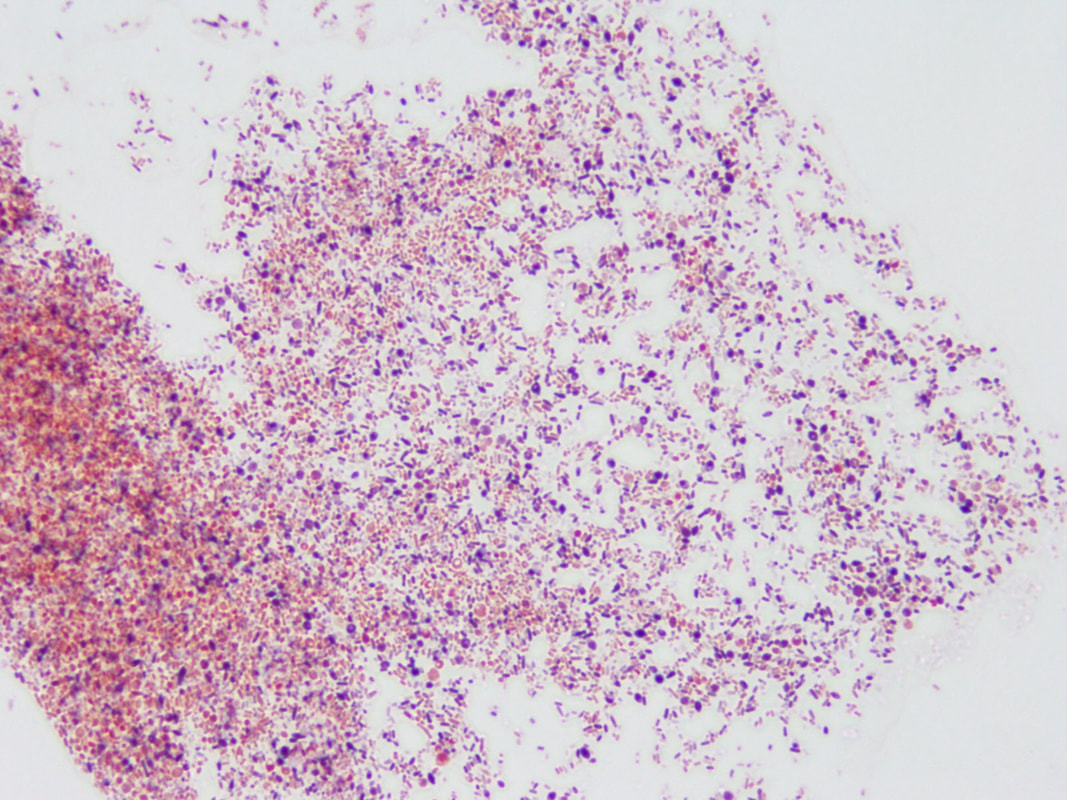

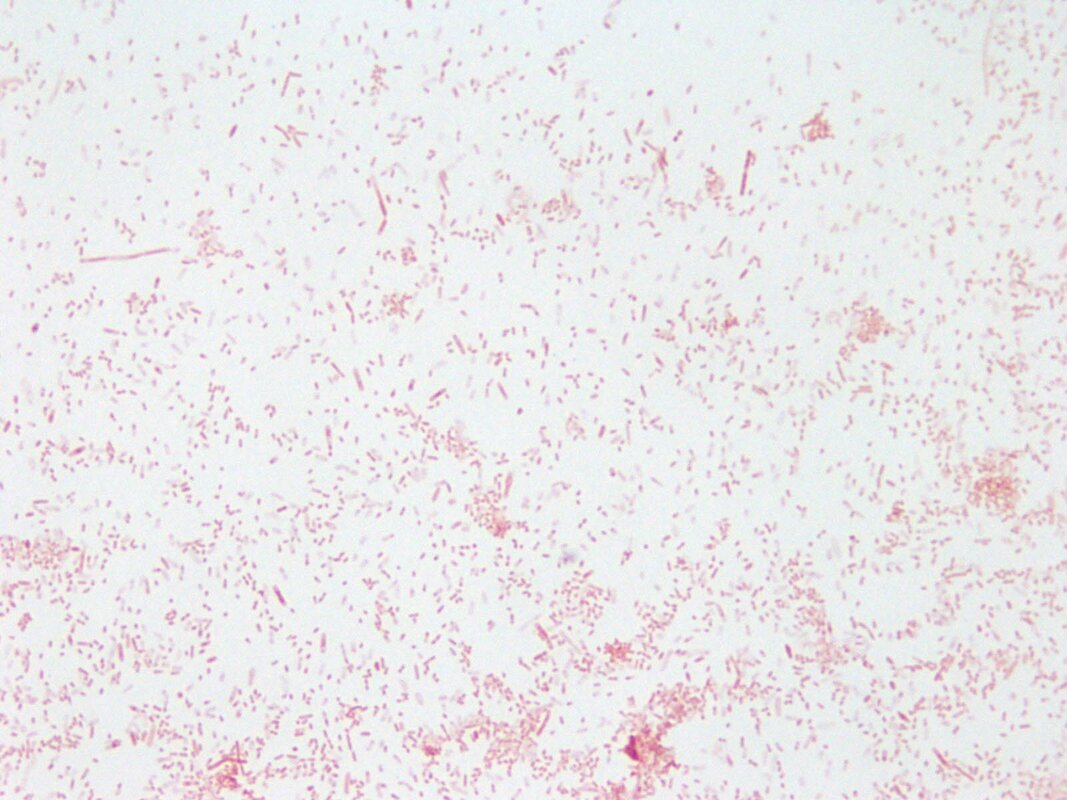

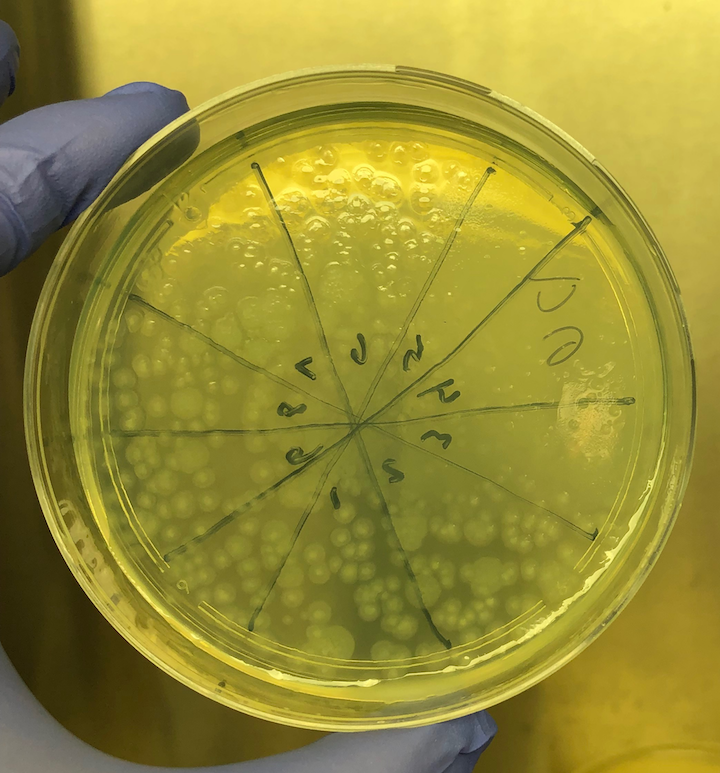

Propionibacterium (now Cutibacterium) acnes, Lactobacillus, Borrelia burgdorferei, and a few others. (This work is covered by the provisional US Patent Application #62785377, filed 12/27/18.) We took cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from 14 patients with MS (and other demyelinating diseases) and compared the CSF to a set of four controls who had no active infection at the time of collection. Among these 14 patients, the CSF from seven reacted against Akkermansia. This includes one patient whose first CSF sample did not react but a second sample, taken three weeks later, was strongly reactive. This patient developed anti-Akkermansia antibodies in his spinal fluid over the course of a few weeks, one chilling aspect of the process of this terrible disease. Interestingly, we also collected spinal fluid from three patients who had had brain biopsies, so we had some idea about what microbes we might find. Two of these three patients had RNA sequences that mapped to Akkermansia. We detected anti-Akkermansia antibodies in their CSF, more than five years after their initial attack and brain biopsy. (Antibodies are stable and long-lasting but they are cleared in months, not years.) For the other patient, we did not detect Akkermansia in the brain tissue, and no antibodies against that bacterium appeared in the cerebrospinal fluid. My team believes our evidence shows Akkermansia may be the cause of ongoing MS in research subject 019. That's one patient, with one traceable link to a bacterial cause of MS. Yes, the numbers are small—the number of MS patients whose CSF we examined, the number of controls, and the number of studies completed—but the findings are compelling so far, and worth exploring. My colleagues and I want to examine the oligoclonal bands (OCBs) in those two patients with Akkermansia RNA and antibodies in CSF against it. With time and funding, we hope to do exactly that kind of encompassing research. You won’t be surprised to hear that testing for oligoclonal bands requires specialized techniques involving the absorption of antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid. Very expensive tests that are, again, so worth pursuing. Could the oligoclonal bands prevalent in MS patients be directed against bacteria? Sure, no one has tested for it. We plan to. The field begs for extensive inquiry and research. Still, even if the OCBs are proven to be directed against bacteria, we can’t guarantee that treating those bacteria directly will improve the disease. We might, as with neurosyphilis or neurologic Lyme disease, be able to limit the damage. But often the neurologic deficits do not reverse. In full disclosure—and if you’ve read this far, you are able to withstand the bumps and bruises that medical research delivers—bacterial infections in the brain may actually “trigger” MS, setting off the disease, then vanish like a ghost. Or those bacterial infections might stay and fester, causing progressive MS. Or new infections might occur, causing relapses of existing MS. In every one of these instances, case-specific bacterial diagnostic tools would be very helpful in our campaign to help MS patients. I will be pursuing this bacteriological line of inquiry in my research and in this blog until the real culprits of MS step forward to claim their ignominious prize: the causal actors in MS. You can help by donating to our MS research, writing to the National MS Society about the importance of this research, and sharing this blog on social media. The more minds we get searching for the cause of MS, the better. Thank you for your interest! All images are from our Microbes in MS research lab.

0 Comments

|

AuthorDr. John Kriesel is Associate Professor of Infectious Diseases at the University of Utah School of Medicine. He began this blog to raise awareness and generate discussion about the possible causes of multiple sclerosis. Archives

March 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed